Monday was the 70th anniversary of the first ascent of Sagarmatha, Chomolungma, Mt. Everest, a fact I’d forgotten till I stumbled into news about a gathering that very day to celebrate it.

It took me back.

**

Twenty years ago—how strange it is to type these words—I was in Santa Barbara, California, on the 50-year mark. I probably wouldn’t have even known it, but there was a Sherpa family living in the apartment complex where my mother and I stayed.

So much of that time is a blur. I had gone to the US to look after mom, who had just received a terminal cancer diagnosis. It was sudden, and fast; the prognosis was four months and she lived for four months and a week.

Like I said, so many things about those months are lost to me now, between the emotional shock and the business of navigating the medical and practical details in a new-to-me country, and yet some things stand out. I remember the Sherpa woman brought over some momos she’d made and I kept them in the freezer and ate them a few at a time; it was such a kind gesture. She also had a baby with impossibly adorable cheeks.

On May 29, 2003, her and her husband invited me along to an event they were attending to commemorate the first ascent of Mt. Everest. An eminent Nepali mountaineer was in attendance that evening—Ang Rita Sherpa, if memory serves, but I can find no confirmation of this online, so it could be another from that era—and I’m sure there were other climbers, too, but it’s not an evening I have a clear memory of. It was one of the few times I left my mom in someone else’s care and went out for a night—it may even have been the only time—and I was at an event surrounded by people from a place I loved and that I didn’t know, in that moment, if I would ever get back to. Or indeed how I would live my life at all once it was over, once she was gone.

**

I had plans for Monday evening, but I ended leaving the house early to first spend a few hours at Astrek Park in Thamel, where the event was being held.

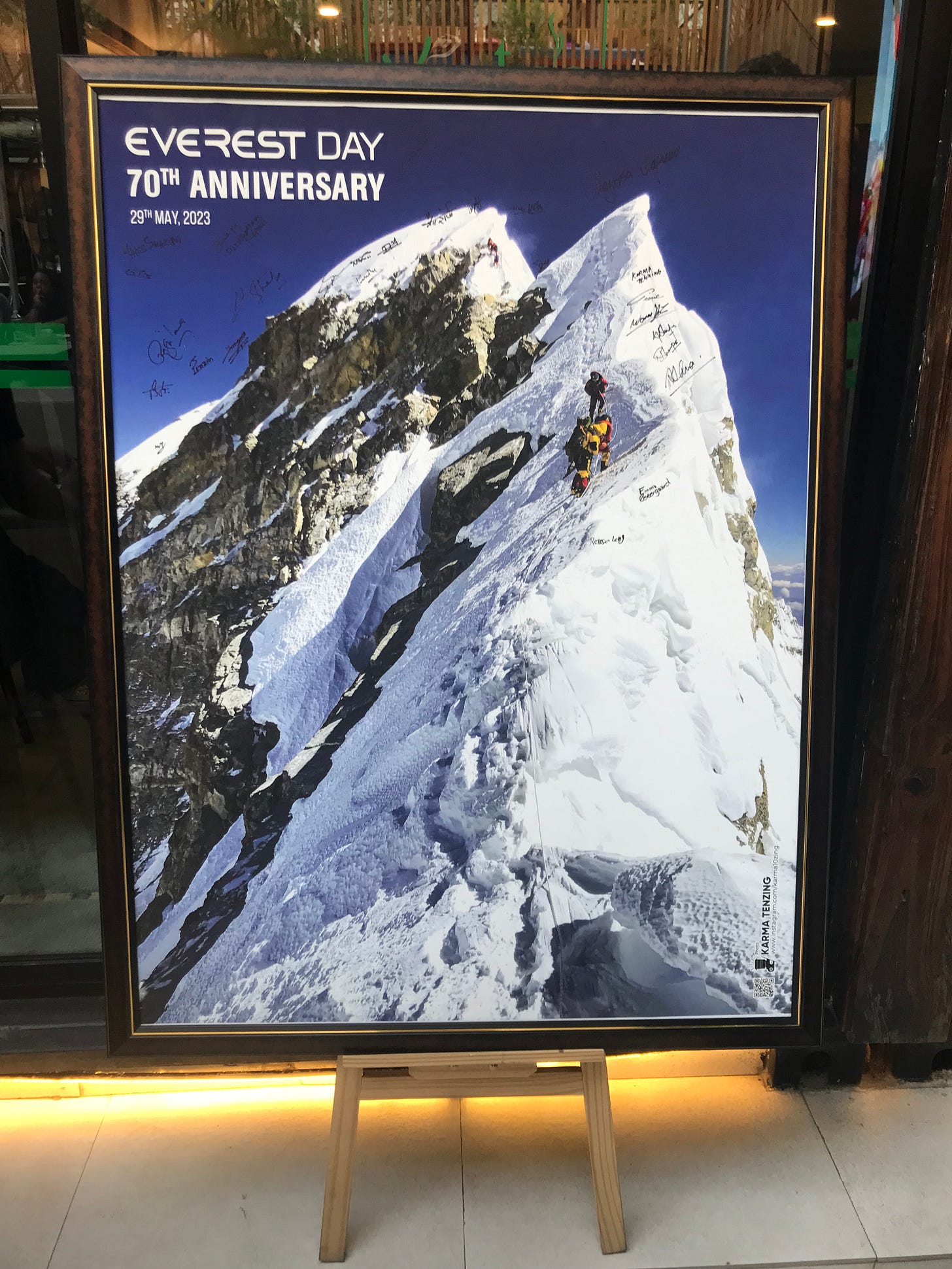

Near the rear of the venue, past the two climbing walls, a desk was set up with a clipboard: summiteers filled in their names, received a commemorative plastic-and-metal pin, and then signed a picture of Everest—there was something kinda fabulously mundane about the process versus how many there were of them. [They were signing the image above, though I took that before it really filled up, over the two hours or so I was there.]

Arrivals didn’t let up and soon every other person seemed to be wearing a pin, and such a variety there were; I’ve spoken before about my love of people watching, and this was a treasure trove.

The woman in tiny, cut-off shorts, cigarette dangling—quite literally—from her fingers, who announced, as she filled in her name on the list of summiteers, that she was the first woman from her country to have done so. Even after all these years, people are still hunting firsts on the tallest mountain on earth. And finding them.

Some meters away I saw a Sherpa climber I’d met briefly at the domestic airport while on route to Phaplu in, I believe, 2001. He was then a record holder, though I thinkit has now been surpassed. Silver haired and broad shouldered, he cut a distinguished figure, virtually an elder statesman of mountaineering, standing amongst his friends and peers. I didn’t think We met once in an airport merited reigniting our acquaintance.

I did exchange a few words (and get a photo) with the poised and charming Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita (who while a summitteer in her own right, is not to be confused with her namesake, the first Nepali woman to summit Everest, who died on the descent).

But mostly I sat with a beer and enjoyed the atmosphere as folks milled around, delightedly catching sight of, calling out to, hugging, and catching up with, each other. For many, it had clearly been a while, and there was that feeling of a reunion between old friends after far too long.

From where I was watching, I ended up not far from a middle-aged man, sporting both a summitteer pin and a tshirt of another Himalayan peak he’d just climbed. And after trying at first to gently convince me that I, too, could summit Everest if I wanted to—strangely, this is something I’ve been told before, by another summiteer; I’m not sure why they think it’s so accessible, but there you go—we ended up on the subject of his homeland, a country not exactly known for its openness; I had asked if mountaineering was popular there. He explained that adventure sports were indeed extremely popular, and not just because of a love of nature. It gave young people, in particular, an avenue to mix and mingle, an escape, and his face was lit up happily, his hand miming the word escape as he said it. I’m still thinking about it.

**

My uncle summitted Everest twenty years ago, around this same time of year, weeks before mom died. At the simple graveside service, he held up a small rock from the mountain as he spoke, then put it in with her.